How does

early-life stress change brain development?

How do these changes mediate increased risk for depression

and other psychiatric syndromes?

Our research is focused on understanding how stress across the lifespan alters the cellular and molecular landscape of the brain, and how these changes ultimately increase risk for psychiatric disorders. Millions of children experience some form of early-life stress, from abuse or neglect to the loss of a parent or exposure to community violence. Early-life stress sensitizes, or primes, response to future stressors, which in turn increases the lifetime risk of depression, suicide, and mood, anxiety, and substance use disorders with a magnitude that far outweighs any known genetic risk. We are focused on understanding the mechanisms of this heightened stress sensitivity as a possible therapeutic target for intervention prior to onset of psychiatric disease.

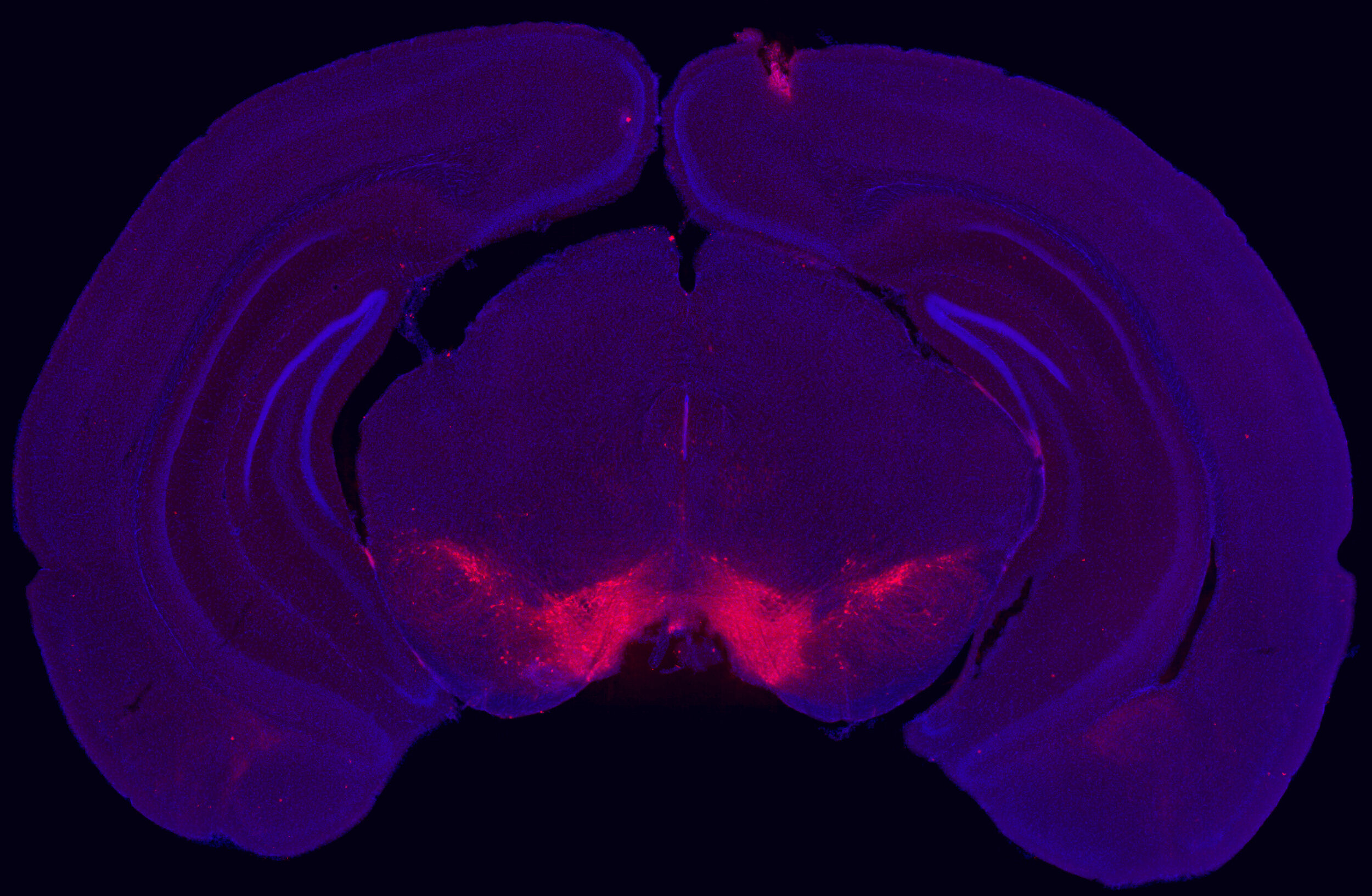

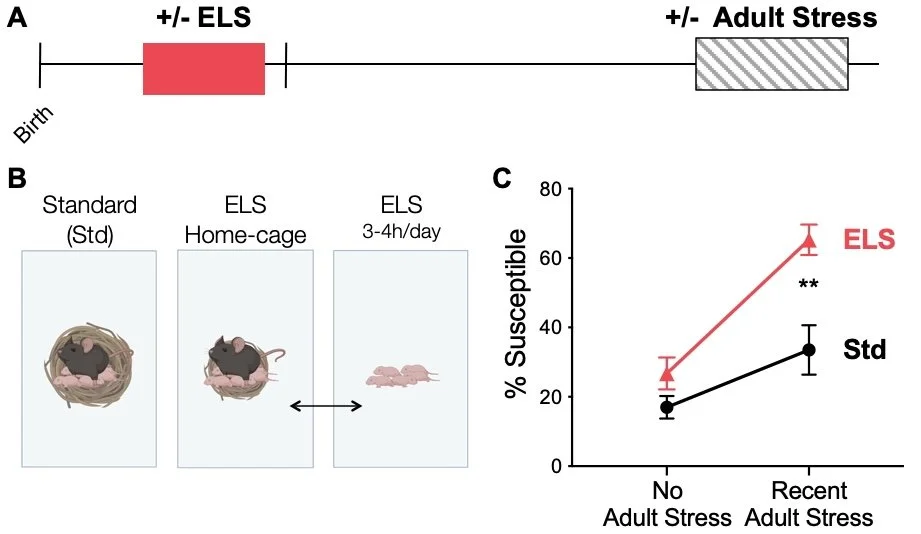

Mouse models of stress and depression

To study the molecular correlates of lifelong stress vulnerability, we use a “two-hit” stress paradigm in mice in which early life stress in a sensitive window increases susceptibility for depression-like behavior, but only after experience of additional stress in adulthood. In lieu of a "HAM-D for Mice," we test responses across a battery of tests of depression-like and anxiety-like behavior.

Genome-wide approaches

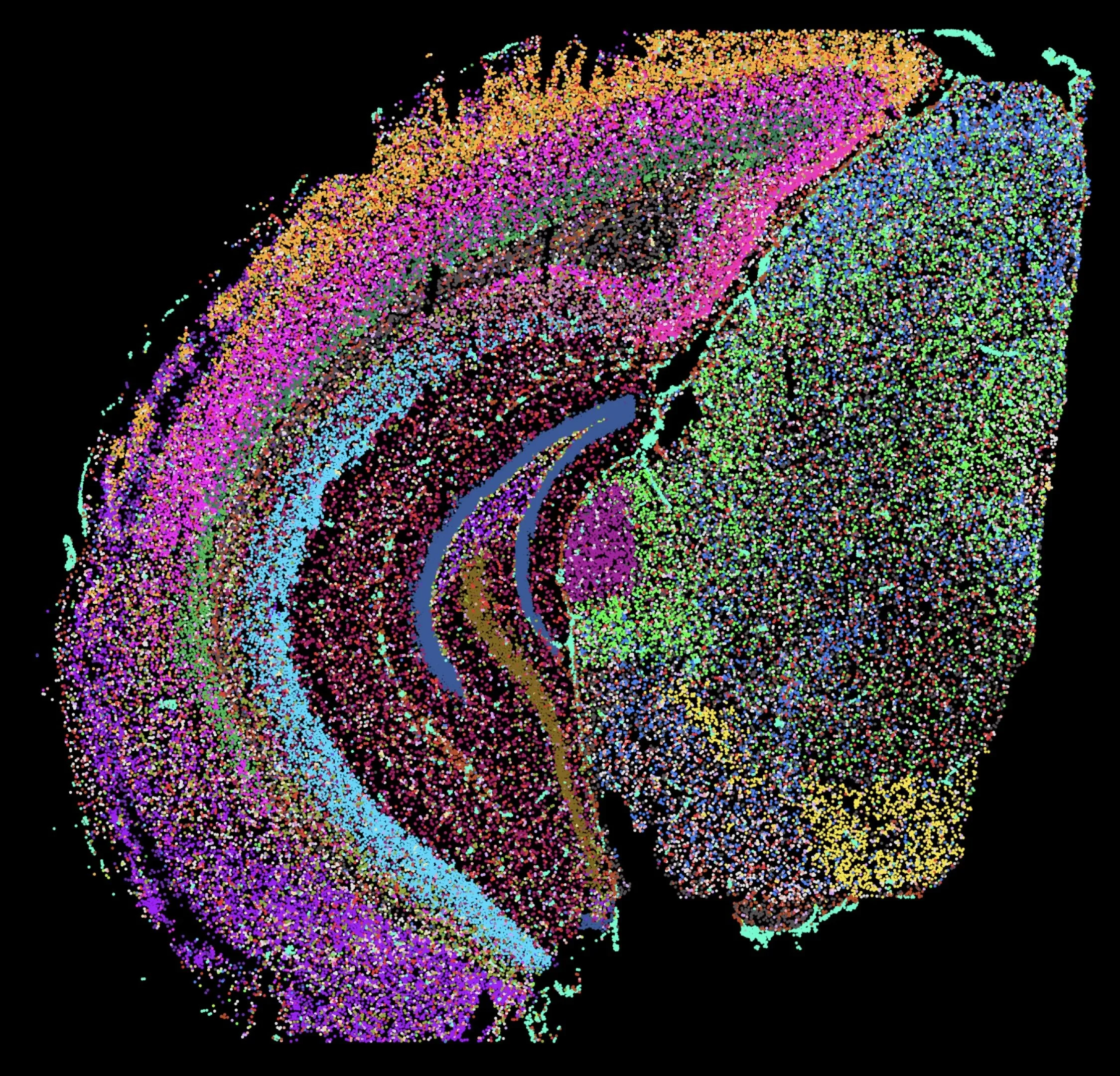

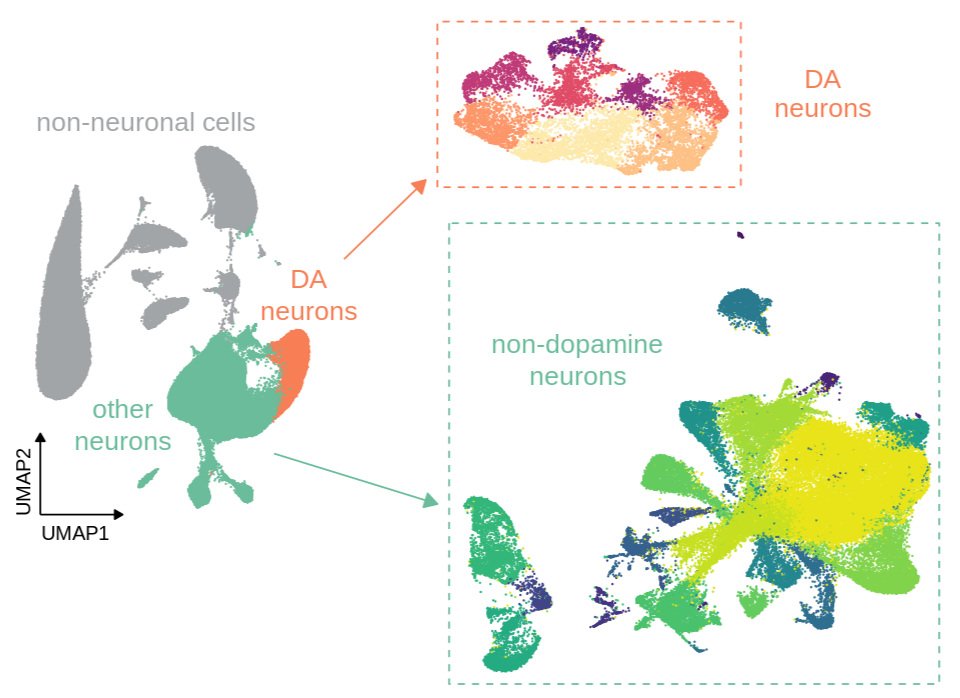

Our previous work used bulk tissue RNA-sequencing to identify broad and long-lasting transcriptional changes in brain reward regions implicated in depression-like behavior. Two interesting patterns emerged, which we are now investigating. First, even prior to behavioral changes, early life stress programs depression-like gene expression patterns similar to those from mice exhibiting depression-like behavior after adult stress. Second, early life stress programs a latent, unique transcriptional response to adult stress among a subset of genes. These important transcriptional patterns could only be revealed through the use of RNA-seq, highlighting the unique power of such approaches. We are now working to understand how these patterns emerge and propagate across development in a cell-type-specific manner.

Current projects are investigating the role of epigenetic modifications in regulating these patterns of transcriptional change and response to future stress. We are applying a combination of powerful proteomic, snRNA-seq, ATAC-seq, micro-C and bioinformatic approaches to understand how early-life stress alters brain development through transcriptional and epigenetic processes. We have discovered that early-life stress primes genomic enhancers by opening chromatin and marking them with the histone modification H3K4me1, which in turn facilitates gene expression response to later adult stress. These epigenetic changes are mediated by an increase in the enzyme Setd7. Using viral-mediated gene manipulation, we have shown that augmenting juvenile Setd7 enhances neuronal firing/excitability (in collaboration with Dr. Meaghan Creed, WashU), and ultimately behavioral hypersensitivity in response to adult stress. Inhibiting reactivation of early-life stress-activated neurons restores normal behavior, providing evidence that stress hypersensitivity is encoded within neuronal ensembles.

We are now working to understand how stress alters cell-type-specific developmental trajectories within the ventral tegmental area, and how stress changes the 3D architecture of chromatin to prime stress response.

Interactions between stress and thyroid hormone signaling

We recently discovered that thyroid hormone signaling connects the molecular cascade between experience of early-life stress and suppressed Otx2 in the VTA. Thyroid hormones represent a translationally relevant and tractable target to ameliorate the pleiotropic effects of early life stress. We have several ongoing projects focused on understanding how thyroid hormones mediate the long-lasting impact of early-life stress on brain development and sensitivity to future stress.

Male striped mouse huddling with a pup. 📸: Todd Reichart

The neurobiology of caring vs neglectful/abusive paternal behavior

In addition to understanding the consequences of early-life stress, we have leveraged a non-traditional bi-parental rodent species, Rhabdomys pumilio (African striped mice) to understand the neurobiology driving caring vs neglectful/abusive paternal behavior. We recently discovered that group living increases the signaling peptide Agouti within the medial preoptic area of the hypothalamus, which suppresses melanocortin receptor-mediated neuronal activity in response to pups, and in turn drives infanticide. In contrast, solitary living suppresses Agouti, allows MPOA neuronal activity, and promotes caregiving. This work reveals a previously unknown role for Agouti as a molecular integrator of socio-environmental information to govern parental investment. With Dr. Ricardo Mallarino (Princeton).

Translational Impact

Our work is translational and collaborative, extending from basic mechanistic studies in rodents to work with human subjects and patient datasets.

Artwork by Mike Cassal

In collaboration with Dr. Dylan Gee (Yale), we investigated how the experience of early life trauma sensitizes Central American and Mexican children to stressful immigration experiences such as family separation during detention in ICE and CBP facilities at the southern United States border. (Read more in this Atlantic exposé, including an interview with Peña Lab alumna Anne-Elizabeth Sidamon-Eristoff, who led this study.) This work crosses disciplinary boundaries to provide evidence for humanitarian work directed at helping children and families displaced by war and violence.

We have also leveraged cross-species RNA-sequencing data from mice and humans to show that depressed individuals with a history of early life stress respond differently to antidepressant treatment due to altered gene expression signatures in the brain, particularly among female subjects. Genes regulating chromatin remodeling and organization were among the most dysregulated. These findings provide evidence that depressed patients with a history of early-life stress may constitute a unique sub-population of patients that require unique treatment based on altered transcriptional state in the brain.

In collaboration with Dr. Dan Notterman (Princeton) and Dr. Barbara Engelhardt (Gladstone), we are working to determine how different forms of childhood adversity impact DNA methylation signatures in the Future of Families Child Wellbeing Study, a cohort of children with high occurrence of adversity, This work critically extends earlier studies by modeling whether differential methylation is expected to have a functional impact on gene expression, and examining tissue-specific expression of affected genes.

We are committed to working with a range of scientists across traditional disciplinary boundaries to achieve real-world translational impact.